Sampling Some Smackin’ Sunflower Seeds

Feb. 27th, 2026 06:33 pm I used to eat sunflower seeds when I played softball as a kid, and I can’t say I’ve ever eaten them since. For some reason, I was getting advertisements for Smackin’ Sunflower Seeds on Instagram. In that moment, I thought, you know what, sunflower seeds sound kind of good to snack on right now.

I used to eat sunflower seeds when I played softball as a kid, and I can’t say I’ve ever eaten them since. For some reason, I was getting advertisements for Smackin’ Sunflower Seeds on Instagram. In that moment, I thought, you know what, sunflower seeds sound kind of good to snack on right now.

I would say in my life I’ve only had regular sunflower seeds, ranch, and BBQ flavored, so when I saw Smackin’s array of flavors, I was certainly intrigued. I am someone who believes variety is the spice of life, so of course I couldn’t choose just one flavor. I went ahead and bought a variety pack that included all their flavors (except the OG Original), and my dad and I gave them all a try.

I let my dad pick the first flavor we tried, and he chose “lemon pepper.” These definitely had a strong flavor, as advertised, and the taste actually reminded me a lot of a steakhouse. The peppery-ness wasn’t overwhelming, and my dad and I gave these ones a 6.5/10.

Up next, we went for a classic: Ranch. The ranch flavor reminded me a lot of a Hidden Valley Ranch seasoning packet, like the kind you mix into dips or salad dressings. Surprisingly, the ranch flavor was very subtle, which is certainly something that ranch never is. You get a Cool Ranch Dorito and that shit is RANCHED UP. In the case of these seeds, I could’ve used more ranch flavor. They were kind of weak, but the flavor that was present was good. These were a 6/10 from both of us.

We switched to a sweet flavor, their Cinnamon Churro. This flavor was actually really nice, it wasn’t just straight cinnamon, it had that nice churro-vanilla sort of flavor. I will say that the flavor wasn’t very long lasting, though. Like it wore off very quickly. The taste, while it lasted, was very nice and not too sweet, with just a little bit of saltiness to have a nice sweet-and-salty factor. This was a 7.5/10 from my dad and a 7/10 from me.

My dad wanted to get the Cheddar Jalapeno out of the way, since he feared it would be really hot and we’re not exactly known for loving spicy stuff. I’m happy to report that while these ones do have a real kick with a heat that lingers just a touch, it has a really nice actual jalapeno flavor and isn’t just hot to be hot. While there’s not so much of the cheddar flavor present, if you’re someone who likes a little bite in their snack, this one would be a great pick for you. I wouldn’t eat a whole bag, but they were pretty tasty. These were a 7/10 from both of us.

Onto Dill Pickle, which was one I was very excited for. Lemme just say, these bad boys were picklelicious. These had a super solid, bold pickle flavor that was very enjoyable and not too acidic, just had that nice dilly briny taste. These ended up being in my top two favorites overall, and we both gave them an 8.5/10.

Over to the Cracked Pepper, I was curious how this would compare to the Lemon Pepper. If you are someone who puts so much pepper on their steak or eggs that people around you are sneezing to high heaven, then this is the flavor for you. These were so peppery, like pretty overwhelmingly so. I honestly didn’t care for them, and gave them a 4/10, but my dad gave them a 6/10.

Next up was the Backyard BBQ. I do love barbecue chips, so I was looking forward to see how these compared flavor-wise. The BBQ was super bold! Just one seed was absolutely packed with BBQ flavor, and it was very tasty! More long-lasting flavor and very strong, these were super good and ended up being another favorite. My dad gave them an 8/10 and I gave them an 8.5/10.

Back to the sweet ones, we tried the Maple Brown Sugar. Like the Cinnamon Churro, they were really nice but not long-lived. They’re a bit subtle, like not a huge amount of maple flavor or anything, but still pretty good. My dad gave them a 7/10 and I went with a 6.5/10. The rating would be a lot higher if the flavor lasted longer or was stronger.

Starting to wrap up our sunflower adventure, Sour Cream and Onion was next. These tasted so classic and recognizable, like if you enjoy sour cream and onion chips, these are for you because they taste absolutely spot on. They honestly reminded me a lot of Philadelphia Cream Cheese Chive and Onion flavor. These were a 7.5/10 from both of us.

The final flavor before trying the mystery flavor was Garlic Parmesan. These were super garlicky, but didn’t offer up a whole lot of parmesan flavor. The garlic really stole the spotlight here, but it was still a tasty flavor, earning it a 7/10 from both of us.

Finally, the mystery flavor! I truly had no idea what to expect. Do you know how DumDums make their mystery flavors? Well, I can only assume that Smackin’ does the same thing, because the mystery flavor tasted exactly like the Cheddar Jalapeno and Ranch mixed together. It was like the Cheddar Jalapeno but less hot, and somehow even better! The mystery flavor earned an 8/10 from both of us.

Well, there you have it! Eleven flavors of sunflower seeds. The only one I didn’t get to try that I would’ve loved to is Cheeseburger! Honestly, these were pretty solid sunflower seeds. It felt kind of nostalgic to eat them, even if they are kind of tedious to get through. I felt like one of those dogs that has a “slow down” bowl because you can’t just plow through them like chips or crackers.

Anyways, if you’re interested in trying some for yourself, I have a 10% off code for you! Yippee!

Which flavor sounds the best to you? Do you eat sunflower seeds often? Let me know in the comments, and have a great day!

-AMS

Who ARE these people

Feb. 27th, 2026 03:34 pmThis seems somehow to link on to earlier posts this week - a lot of my memories of childhood reading/being read to are associated with episodes of illness!

Posted in a group on Facebook: 'A book you read as a child yet still think about today'.

WOT.

Just So Many.

The various classic works of children's literature that have become culturally embedded in references and allusions - the Alice books, the Pooh books, The Wind in the Willows, the Jungle Books, The Secret Garden, Little Women et seq, the Katy books -

Ones that are perhaps not quite so iconic? like the Little Grey Rabbit books.

A whole mass of girls' school stories and pony books. A fair amount of Enid Blyton though I'm not sure I think about any specifics there.

Various anthologies and collections - some stories still remembered - classic fairytales, myths, etc.

Plus things like Pears Cyclopaedia and The Weekend Book

And I do, in fact think about things like, the attitude towards The Scholarship Girl in The Making of Mara in what is actually the unposh, girls' day school, to which her father sends snobbish Mara. (Only this week when thinking about educational privilege....)

Plus, I will mention yet again being absolutely traumatised by Marie of Roumania's The Lily of Life.

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon

Feb. 27th, 2026 09:06 am

The Sicilian debacle leaves Syracuse with seven thousand Athenian prisoners slowly starving in a quarry. What better time to stage a play?

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon

The Big Idea: Bernie Jean Schiebeling

Feb. 26th, 2026 09:11 pm

Like blue eyes, height, or left-handedness, how much of our temper and ill manners can we contribute to our genetics? Author Bernie Jean Schiebeling explores the breakage of inherited anger, and what it’s like to fall victim to the temperament our parents passed unto us in the Big Idea for their newest novel, House, Body, Bird.

BERNIE JEAN SCHIEBELING:

My great-grandfather was not a good man.

Without getting into too many details, he was angry and abusive, so much so that my great-grandmother was able to divorce him in the late 1920s without too much trouble. After the divorce, my great-grandfather left—possibly fled—and then committed a string of burglaries across Kentucky and Tennessee while working as a door-to-door salesman. Many years later, my father met one of his ex-colleagues, who said the man had been incredible at sales. Less so at stealing, since he kept getting caught. “And,” he said, pointing at my dad’s breakfast plate, “I can tell you that you take your scrambled eggs the same way. So much pepper.”

Dad never met my great-grandfather (even Grandpa hardly knew him, since he was just a toddler during the divorce). But they both liked peppery eggs, and so do I.

Other echoes persisted too. Anger sometimes exploded from my grandfather, though less than the previous generation. My dad is calmer than his father, and I am calmer than him. Still, rage sometimes rises in me with the inevitable force of a king tide. I hear the ocean rushing in my ears—

—And I breathe through the impulse. I don’t have to do this. I don’t have to continue this tradition that—I hope—none of us wanted.

Inheritance is never clean. We gather too much over the course of a life, too many objects imbued with too many memories, to ever pass on an uncomplicated story to our descendants. In most cases, this is a gift, the last we give to our loved ones. Sometimes, however, it is a weapon, sharp-edged and dangerous to hold, and we have to figure out how to carry it anyway, or how to put it down in a way that hurts no one else. This is the big idea of House, Body, Bird.

The idea was larger than I expected. I didn’t mean for this to be a novella; I thought it would be a short story too long to sell to most markets, like most of the work I have in my drafts folder. I was about 15,000 words deep by the time I realized I was writing a book.

In retrospect, I shouldn’t have been that surprised. Stories find their ideal length through their subject matter, and the more I thought about House, Body, Bird’s family and their home-slash-haunted-dollhouse-museum, the more I realized that the sheer amount of stuff in main character Birdie Goodbain’s inheritance—both dollhouses and the history behind those dollhouses—needed to show up on the page. I started including imagery wherever I could: descriptions of dolls, of difficult memories, of how haunted the body becomes from those memories. In the story’s earlier scenes, I wanted to crowd Birdie, make her tuck her elbows in as she navigated the rambling, watchful house.

Of course, this is only the first half of the difficult-inheritance-problem, the “Someone has willed me a weapon” half. I still had to find a good way to explore the second half of “Thanks, I hate it.” Birdie couldn’t stay scared. Thankfully, I had a solution; I just needed to reorganize some clutter.

When I first started writing the would-be short story, I had alternated between two point-of-views for Birdie, third-person limited and first-person. This created emotional whiplash as Birdie went from a meek third-person POV ruminating on the house’s creepiness to a furious first-person POV bashing through the walls with a meat tenderizer. By grouping all the third-person scenes together and following them with the first-person ones, Birdie had much cleaner character development. It’s relevant that the switch in perspective happens once Birdie commits to escaping and seizing her freedom. In that moment, she moves from third-person, where an unseen narrator observes and objectifies her (like a doll!), to first-person, where she narrates her experiences. While imagery had pushed up against the margins in the third-person section, Birdie’s opinions, observations, and memories pepper her own telling of the story. She gets space to breathe.

In keeping with the novella’s spirit of excess, Birdie’s sections are interspersed with ones from the haunted house’s point of view. Originally, this was useful because it allowed me to reference the previous Goodbain generations with a level of detail that wouldn’t have been possible for Birdie, but the house eventually became the story’s second emotional heart. Although I worried about overwriting throughout the drafting process, a maximalist approach to storytelling was what I needed for House, Body, Bird.

It’s funny—early on in the story, Birdie’s messed-up dad tells her, “We build, and build, and build.” The Goodbain family built and built and built their house as a way to create a family narrative worth passing on, as an attempt to build livelihoods and lives and love, and I did the same thing. I built and built and built the story to understand how Birdie’s family history loomed over her, and how she could create a new, more loving life in response to it.

House, Body, Bird: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Books-A-Million

Oh, Look, an Airport

Feb. 26th, 2026 02:54 pm

Strange how I keep ending up at one.

This time, however, not on business. Visiting friends because now that the novel is in I can do that. I’ll be traveling on business very soon, however, first to San Antonio and then to Tucson. The life of an author is strangely itinerant.

— JS

Odds and ends

Feb. 26th, 2026 06:14 pmI've posted occasionally about Maria Sibylla Merian, this sounds like an interesting book on her and her art.

***

The funding to save the area surrounding the Cerne Giant for the National Trust has been raised: any further donations will go to habitat creation and increasing access.

***

Exhibition: North Staffordshire Miners’ Wives Action Group Archive (formed in response to the 1984 miners’ strike,members have been actively campaigning for over 40 years).

***

Martyrdom, Misrepresentation and the ‘Tolpuddle Martyrs’ (I was at uni with a Loveless descendant). And I discovered that the Internet Archive has a recording of the BBC Home Service broadcast of Miles Malleson and H Brook's Six Men of Dorset.

***

More rather horrifying reports coming out about the surrogacy industry: Embryo couriers, student egg donors and cut-price surrogates. Journalist Alev Scott investigates northern Cyprus’s booming baby business — where Brits head for cheap treatment, gender selection and lax legislation.

***

The National Archives is hosting the exhibition 'Love Letters', exploring 500 years of expressions of love. This exhibition captures the voices of paupers and monarchs, reflecting friendships, romance, and more. But why does love appear in government documents?

***

Recovering “Lesbian” Voices in the Middle Ages: Twelfth and Thirteenth Century Germanic Mystics.

***

The Rohonc Codex: Hungary’s Mysterious Manuscript That No One Can Read

***

Five Science Fiction Stories About Investigating Enigmatic Artifacts

Feb. 26th, 2026 10:04 am

"What is this thing, and where the heck did it come from?" is a great way to start any story!

Five Science Fiction Stories About Investigating Enigmatic Artifacts

Hell’s Heart by Alexis Hall

Feb. 26th, 2026 08:37 am

What better cure for melancholy than to serve under a captain whose obsessed pursuit of a leviathan will surely doom all involved?

Hell’s Heart by Alexis Hall

The Big Idea: Jeff Somers

Feb. 25th, 2026 05:01 pm

Five funerals may seem like a lot, but this number is actually cut down considerably from author Jeff Somers’ original idea of 26 deaths. Put on your best black tie and follow along the Big Idea for his newest choose-your-own-adventure, Five Funerals.

JEFF SOMERS:

WHEN I was 14 years old—chubby, prone to wearing tie-dye t-shirts for no known reason, and gifted with inexplicable levels of confidence—I wrote a novel in just under three months. Nothing’s impossible when you have no job and live on a diet of Cookie Crisp cereal and RC Cola, and the whole writing thing is so fresh and new, you haven’t yet developed a nose for your own bad writing. Writing novels sure is easy, I thought, and for a long time I actually believed that.

35 years later, I was staring up at a poster of Edward Gorey’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies that I’ve had since college. If you’re unfamiliar with The Gashlycrumb Tinies, it’s a parody of old-fashioned alphabet books depicting how 26 blank-faced, Dickensian children die via gorgeous, intricate drawings and a series of simple rhymed couplets. I’ve been fascinated by it for most of my adult life, and I wondered what those doomed little urchins were like, how the full story of their freakish deaths would actually play out.

In other words, I wanted to write a novel about them. As with most of my thoughts, this seemed pretty brilliant to me (the inexplicable levels of confidence have only inexplicably increased with age), and somewhere in the background there was 14-year-old Jeff whispering yeah, and writing novels is easy!

Five years later, I’d filled a hard drive with trash.

It was a problem of structure: If you do the math, in this story, 26 people have to die in horrible, hilarious, darkly whimsical ways. Is 26 deaths in a single novel a lot? It is! Especially when each death needs to have unique elements and a lot of focus and page-time.

I tried structuring it like a detective novel, with one of the characters trying to figure out why all their old classmates were dying. But this quickly became repetitive—there’s a reason detective characters usually don’t investigate dozens of separate murders. You either wind up with a 1,000,000-word novel or you have to cut some corners.

I tried a draft where the deaths happened in chronological order. But this approach got tedious, because I was introducing characters just to kill them. While this was a lot of fun, it didn’t feel like a novel, like a complete story. The collapse of this draft did give me an idea, however: Short stories.

Anyone who has ever talked writing shop with me, or attended one of my Writer’s Digest workshops, knows that I am an enthusiastic short story writer (and reader), and that I regard short stories as the general cure for all writing woes. Any time I run into any sort of writing challenge, from writer’s block to Oh No I’ve Created an Insurmountable Plot Paradox (Again), my immediate solution is to stop trying to write a novel and start writing short stories about the universe and characters. This almost always works and, even when it doesn’t, I usually end up with some good short stories out of the deal. (As all working writers know, short stories are worth tens of dollars in today’s economy.)

So, I started writing stories about each character’s death, as an exercise. I didn’t worry about narrative cohesion, or pacing, or tying the story into the main novel at all. I just had fun writing 26 stories about people dying in variously hilarious, tragic, and sad ways extrapolated from Gorey’s work.

As I did this, I realized what the problem had been all along: Five Funerals isn’t a story about a bunch of kids who die and maybe deserve it. Well, it is that, but it’s also a story about loss. And memory. And how we hold people we’ve lost touch with in a kind of amber in our memories, unchanging and eternal. It was a story about that moment when you hear that someone you used to know—someone you maybe used to love—has died.

In those moments, we experience something strange: That person who’s been preserved in our head suddenly (and violently) transforms. After years or decades of being young and alive in your memory, they’re abruptly aged up—and gone. It’s a sobering, disorienting experience, and I realized that’s what I wanted Five Funerals to be—a funny, dark, hilarious story that mimicked that sense of the past rushing forward to catch up with the present.

The short stories I’d been writing evolved into a choose-your-own-story engine, disrupting the reader’s groove and forcing them to reckon with the sudden, unwanted knowledge that this character had died. And since no one experiences time or loss the same way, readers can choose how they experience it here: When a name is flagged with a footnote in the novel, you can choose to flip to the story it’s pointing to—or not. If you do, you might find out how that character died, or discover a bit of funny or heartbreaking backstory.

You can keep following the chain of deaths, or you can return to the story where you left off. Or you can ignore all the footnotes and just read the book straight through, or randomly, or in sections. Just like we all grieve in our own way, you can read Five Funerals in your own way.

The end result, I think, is a book that explores how time slowly strips those yellowing old memories away, replacing them with the harsher truth of death and loss. Even if those losses are sometimes so weird and unexpected that you have to laugh.

Five Funerals: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Bookshop|Apple Books|Kobo|Ruadán Books

Author socials: Website|Instagram|Bluesky|Threads

Additional links: Animated cover on Instagram and on Bluesky.

I mean, I feel strongly that you will all be happy with a picture of Saja licking his adorable little lips regardless of context, so this is a low-risk maneuver anyway.

I will tell you all about the exciting things one day, I promise you. Just not today. But look! Kitten!

— JS

Bundle of Holding: Good Society (from 2024)

Feb. 25th, 2026 02:54 pm

The Good Society Bundle featuring Good Society, the Jane Austen-inspired tabletop roleplaying game from Storybrewers Roleplaying.

Bundle of Holding: Good Society (from 2024)

Wednesday dutifully attended the Fellows' symposia

Feb. 25th, 2026 06:04 pmWhat I read

Finished Eleven Hours to Murder and went on to Death by the Dozen, which combine the cozy antics of Cat Caliban and her posse with mysteries tending to be rooted in past historical events in and around Cincinnatti. And Cat is after all pursuing a career as a PI, rather than taking up some quirky midlife career and just stumbling over bodies. And her partner is a retired cop who used to work in Juvie, not homicide. So counter to a lot of the recurrent tropes....

Then I realised, oops, that next meeting of in-person book group appears to be next Sunday - though I have not received any further notification since exchange of emails after the last meeting - so I have been reading Anna Funder, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life (2023), which is blurbed as 'genre-bending', meaning it does things I am not that on board with, i.e. the writer's personal stuff/odyssey and b) fictionalising bits as narrative. Though I am marking it up somewhat for her realisation that her Great Hero G Orwell was A Horror. I daresay a lot of his trouble with being basically incapable in managing matters and practicalities was down to class and educational background but you'd have thought he might have cottoned on to some of that? rather than blithely eating up the whole of their butter ration? (fairly minor in the overall marital picture).

On the go

Read a bit more in I Am a Woman but still feeling a bit bogged down, even if Laura has finally had a night of sapphic passion.

Elizabeth George, A Slowly Dying Cause (Inspector Lynley Book 22) (2025). Fortunately this was a Kobo deal. Phoning it in. Also getting rather bogged down. 20% in and only just getting a sight of Lynley, let alone Havers. Includes great chunks of autobiographical reminiscence from the corpse.

Have also made some progress on volume for review.

Up next

Have apparently manifested, in place where I would never have thought to look for it, GB Stern, The Woman in the Hall (1939), which I had been fruitlessly looking for elsewhere, with a notion of maybe recommending for book group, as has recently been reissued for the first time since 1939 by British Library Women Writers.

Babel no Toshokan by Tsubana

Feb. 25th, 2026 08:52 am

What could possibly go wrong with playing along with an unhappy teen's delusions?

Babel no Toshokan by Tsubana

New Meat in a Clean Room edited by Ira Rat

Feb. 25th, 2026 01:00 pm Ira Rat’s introduction to New Meat in a Clean Room is disarmingly candid. He reels off his influences in one long, unfiltered paragraph: Mark Fisher, J. G. Ballard, Joy Division, Francis Bacon, Nan Goldin, Clive Barker, The Cure, No Wave cinema, Cindy Sherman, William S. Burroughs, Siouxsie Sioux, Gregg Araki, Poppy Z. Brite, and many more. The list feels like a private obsession finally shared rather than a calculated pose. Rat even confesses that he is not even sure what the phrase he used when first contracting writers for this project—“hauntological overtones”—even means; it simply captured the mood he wanted. That candor sets the tone for the entire book. The six stories that follow do not merely nod to those influences; they absorb them and produce something remarkably unified. This is not a loose collection of extreme horror. It is a deliberate suite in which post-punk alienation, splatterpunk violence, and hauntological looping converge on the body as the last contested territory. Clean rooms turn filthy. Privacy dissolves. History leaks through the walls like black bile. There is no warmth here, no redemption, only a cold, surgical clarity.

Ira Rat’s introduction to New Meat in a Clean Room is disarmingly candid. He reels off his influences in one long, unfiltered paragraph: Mark Fisher, J. G. Ballard, Joy Division, Francis Bacon, Nan Goldin, Clive Barker, The Cure, No Wave cinema, Cindy Sherman, William S. Burroughs, Siouxsie Sioux, Gregg Araki, Poppy Z. Brite, and many more. The list feels like a private obsession finally shared rather than a calculated pose. Rat even confesses that he is not even sure what the phrase he used when first contracting writers for this project—“hauntological overtones”—even means; it simply captured the mood he wanted. That candor sets the tone for the entire book. The six stories that follow do not merely nod to those influences; they absorb them and produce something remarkably unified. This is not a loose collection of extreme horror. It is a deliberate suite in which post-punk alienation, splatterpunk violence, and hauntological looping converge on the body as the last contested territory. Clean rooms turn filthy. Privacy dissolves. History leaks through the walls like black bile. There is no warmth here, no redemption, only a cold, surgical clarity.

Edwin Callihan’s “Angelhood & Abscission” is the longest story and the one that most explicitly builds the anthology’s shared world. The piece is framed as a series of letters from an unnamed narrator newly arrived in a vast brutalist city. The architecture is rendered with obsessive detail: Buildings rise on “colorless columns and flying buttresses rounded by cylindrical obelisks, spackled with tiny little windows like the outside was hit with buckshot” (p. 10). The narrator finds a sparse apartment with a couch, a microwave, TV dinners, and a television that only catches static or late-night sign-off patterns. The prose circles in the way genuine fixation does. Early on, the narrator visits a bar called Sefer, where a “band” manipulates a chrome box that emits “clanky, metallic groans and whimpers” (p. 8) while oily yolk drips from the stage. He meets Bill, a tall man with a bowl cut and a face covered in red boils, who speaks with a whistling “w.” He is later introduced to The Sculptor, who keeps hundreds of sheet-draped figures in a red-lit basement beneath a twenty-four-hour copy shop. The figures are malformed, not quite human, with blue veins running across marble-like skin. When the narrator reaches to touch one, The Sculptor slaps his hand away and retches. The realization arrives gradually and inescapably: The narrator is being sculpted, too. Callihan balances cosmic detachment with intimate physical detail. Lines like “[b]etween heaven and hell is an orifice, a puckering asshole shitting us out into wherever” (p. 24) land with cosmic revulsion. The closing ascent to the lunar surface—during which the narrator looks down at the city “blinking like Christmas lights” (p. 24) and understands there may be countless versions of himself “plucked and discarded again and again” —is both grotesque and quietly devastating. The repetitive, hypnotic prose mirrors the narrator’s growing dissociation, making the reader feel the slow erosion of self in real time.

Sam Richard’s “Red Tears Are Shed on Grey” shifts to a fragmented, almost cinematic style. Sections marked “C” intercut loops of historical atrocity footage—missiles rising in “tumescent power” (p. 26), faceless soldiers marching, factory fires, hanging bodies, endless ejaculation overlays—with the story of Sasha, a young woman smoking outside an illegal basement venue called the Rat’s Nest. The Karl Marx epigraph about dead generations weighing like a nightmare is structural rather than decorative. The footage is rendered with clinical detachment: faces scratched out, flags clipped, pilots with faces removed. Sasha listens to a strange man reminisce about the venue’s past as an underground library filled with suppressed radical texts and do-it-yourself guides. The conversation unsettles her. When she returns home, the loops invade her reality. She finds herself strapped to a chair by invisible restraints, forced to watch versions of herself on a filthy projector screen. Her face tears open. Blood pours. Tears bleach the screen white. Richard refuses catharsis. The story ends in vacancy and fraying film. The formal choices—abrupt cuts, smokeless cigarettes, eternal ember—create a disorienting rhythm that mirrors Sasha’s unraveling. History is not past; it is a corrupted reel projecting itself onto living flesh until identity dissolves.

Charlene Elsby’s “I’m Not Coming After Her” is the emotional and philosophical heart of the collection. The narrator is the surviving twin speaking from inside the womb after her sister Millie has been delivered and harvested for organs. Elsby writes with extraordinary precision. We feel the initial warmth and nutriment that convinced both twins their mother wanted them to live. We feel the shift when the technician explains that Millie cannot survive independently and that her viable parts could save other babies. The mother’s relief is immediate and physical: “the relief of not having to have two daughters after all, and that it would be through no fault of her own” (p. 49). The surviving twin experiences every scalpel cut, every cold disposal of unusable parts labeled “biological materials.” The decision to remain inside and fester, rather than enter a world that treats bodies as spare parts, is presented without melodrama: “All I must do is fester,” the narrator repeats like a verdict. The story reframes the womb as a battlefield and asks, without sentimentality, whether any world that dismantles you for parts is worth joining. Elsby’s philosophical density never sacrifices visceral immediacy, however. The final description of infected tissue turning gray as blood retreats is one of the most haunting images in contemporary horror. The first-person perspective from inside the womb creates an intimacy that makes the betrayal feel personal.

Joe Koch’s “I Am a Horse” begins in apparently realistic territory and descends into prolonged bodily transformation. An aging mathematics professor, Mr. Sapin, becomes obsessed with a Butoh dancer he first mistakes for a statue in a garden. The story is structured in numbered encounters that escalate relentlessly. The second meeting involves a fake breast torn open during rehearsal. The third is a disastrous dinner in which the dancer accuses Sapin of knowing about her childhood abuse and doing nothing. The fourth finds her at his door soaked in blood. The fifth and sixth dissolve into sensory deprivation: hooded, bound on all fours, fed pureed food through tubes, cleaned by automated jets, slowly reduced to animal state. Koch writes captivity with a poet’s sense of rhythm and a clinician’s patience. The professor’s perverse gratitude amid degradation feels earned rather than contrived. The story refuses easy moralizing. It simply observes the process until the man becomes the horse of the title, rocking gently under an invisible rider who sings a half-remembered lullaby.

The anthology closes with two shorter pieces that function as sharp codas. Justin Lutz’s “Not Waving, but Drowning” literalizes Stevie Smith’s poem inside a flooded basement venue, turning a gig into slow, collective submersion. Brendan Vidito’s “Theatre of Sublimation,” meanwhile, presents a performance in which the audience itself becomes the raw material. Both deny the reader any clean exit.

Certain obsessions repeat across the collection. Clean spaces—operating theaters, copy shops, white-painted Butoh skin—reveal themselves as sites of deepest filth. History loops like scratched film. Privacy is illusory; the body is always subject to sculpture, harvest, projection, or transformation. There is no warmth offered and no redemption promised, only a cold, surgical clarity that refuses to avert its gaze.

Filthy Loot Press has produced a handsome, minimalist object: stark cover art by Rat himself, clean typography, no excess. The physical book feels like the concrete city it describes. In the broader landscape of contemporary extreme horror—where shock often substitutes for substance—New Meat in a Clean Room stands apart. It shares DNA with recent works by Gretchen Felker-Martin, Eric LaRocca, or Hailey Piper, but its intellectual rigor and formal cohesion place it closer to the tradition of Clive Barker’s Books of Blood or Kathe Koja’s early novels. Ira Rat’s editorial hand is confident yet unobtrusive; the stories converse without ever feeling forced.

This is not comfortable reading. It is not intended to be. It is, however, one of the most tightly conceived, skillfully executed, and intellectually demanding horror anthologies I have encountered in recent years. Readers seeking easy scares or traditional resolution should look elsewhere. Those willing to sit with sustained discomfort will find something sharp, lasting, and deeply unsettling.

Low expectations, but apparently not low enough...

Feb. 24th, 2026 02:09 pmI don't expect much from Goodreads, but I was still surprised to learn that Goodreads members have named The Hunger Games as the "best book ever"!

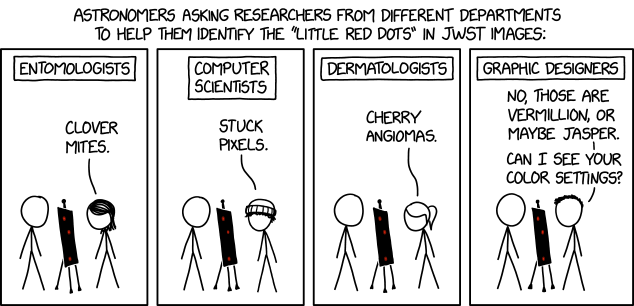

The Big Idea: Danielle Girard

Feb. 24th, 2026 06:05 pm

Motherhood is a term that has many meanings, and looks a little different for everyone. It is also something that comes with a lot of questions, and though she may not have all the answers, author Danielle Girard explores these ideas in the Big Idea for her newest novel, Pinky Swear.

DANIELLE GIRARD:

Most of my novels have begun with a dramatic, explosive scene—gunfire, explosives, or at the very least, a murder. But the premise that caught me by the throat for my latest novel, Pinky Swear, was quieter and in so many ways, much more terrifying.

Pinky Swear is a story about a woman whose best friend agrees to be her surrogate and then, four days before the baby is due, disappears. It was the emotional immediacy of that hook that made it so compelling to write. Not only is the protagonist confronting her fear of losing a child (and one she’s never met) but also the abandonment of her best friend, and the persistent doubts about whether their decades-long friendship was a fraud.

What I didn’t expect initially was how the story opened up issues of motherhood itself. The most obvious ones are the grief of infertility and the question of what motherhood really means when biology refuses to cooperate. But beneath those is the larger theme of what makes a woman a mother? Is it biology? Pregnancy? Blood? Or is it intention, sacrifice, love, and the willingness to show up no matter the cost?

My father was an OB/GYN and, when I was growing up, babies and pregnancies were everyday dinner conversations—the joys and also the heartaches. Today, we seem to live in a culture that often defines womanhood and motherhood by a body’s ability to conceive, carry, and give birth. Infertility can feel like the unspoken failure at every baby shower, in every passing comment and well-meaning reassurance that doesn’t quite land.

In Pinky Swear, the protagonist has already endured that loss. Her inability to carry a child isn’t just a medical fact; it’s an emotional wound that reshapes how she sees herself and her place in the world. Turning to surrogacy is an act of hope, but also an act of profound vulnerability. She must trust another woman not only with her future child, but with her deepest wish.

In this dynamic, the story, rather unexpectedly to this author, became a conversation between devotion and betrayal, selflessness and selfishness. The pregnancy, like motherhood itself, carries an undeniable power, binding the two women together in ways that are both intimate and irreversible. The surrogate’s disappearance forces both the protagonist and the reader to confront uncomfortable truths: that love can coexist with resentment, that good intentions can sour, and that even lifelong promises—such as pinky swears made in childhood—can break under the weight of adult realities.

Writing this book meant sitting with uncomfortable questions. If you can’t carry your own child, are you somehow less entitled to motherhood? If another woman brings your baby into the world, where does ownership of that child’s love begin and end? And if a child is taken from you at the last possible moment, can you still call yourself a mother?

Pinky Swear asks readers to sit with the ache of unmet expectations and the messy, often painful reality of female relationships. It asks us to reconsider the stories we tell about motherhood, and to expand them beyond biology into something more human, more forgiving, and truer — that being a mother isn’t about carrying a child inside your body, but about the deep, resilient power of love, no matter the cost.

As I hope readers will do when they read Pinky Swear, I found myself asking not just what I hope I would do in such circumstances, but who I would be. Bitter or resilient. Closed off or open-hearted. Defined by loss or transformed by it. When the story ends, I believe the protagonist finds herself exactly where she was meant to be, and I hope readers will agree.

—-

Pinky Swear: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Bookshop

Turning Away

Feb. 24th, 2026 10:14 amMeanwhile, ICE is still being tracked throughout Saint Paul (and presumably Minneapolis, but I don't have access to those Rapid Response groups). Reports that I've seen seem to indicate that the majority of the activity has moved out to the less well organized smaller towns and suburbs. Though the "sexy" part of the resistance--the gas in the streets, the violent confrontations--has dried up, the danger to our immigrant communities is far from over. There is zero sense that ICE is actually leaving. They have switched to quieter, more subtle tactics. They've gone further afield. But make no mistake, they are very much still here.

Last night I went to a Singing Resistance meeting for an action that took place this morning. I managed to miss this morning's action because my GPS decided that it wanted to autocorrect Street to Avenue! VERY DIFFERENT, GPS! In fact, a very important distinction!!! So, I ended up getting lost in downtown Minneapolis long enough to miss the gathering time. But, what was interesting to me is that these Singing Actions have, in the past, brought thousands of people into the streets. Famously, they sang songs encouraging ICE agents to defect outside of some of the hotels hosting them. The action today was for rent relief and trying to get the city officials to consider a temporary rent moritorium, something they were very willing to do during COVID, but which they seem less willing to do for Black and brown folks (shocking, I know!) At any rate, I went to the pre-planning/song rehersal last night with

But, this seems to be part of a trend. I'd noticed the day after it was announced that ICE was pulling out, my Food Communists was almost ghostly. Plenty of bags of groceries still needed filling, but the number of volunteers that showed up to do the work was less than half of the normal amount. More people have showed up since, but we are nowhere near our previous number. It seems to be the regulars and the die-hards again--although thankfully the Veterans for Peace are still guarding the doors for us.

I ran into some neighbors yesterday when I was walking home from the Communists and they were returning from a daily protest. They also noticed a significant lack of bodies. People were still there, but the crowd was thinner. It's worrying because we are all still very much holding our breaths.

I guess people are buying into the idea that we won and that it's all over. I mean, I would very much like that to be true? I'm just not sure it is and it's disheartening to see that the energy could not, in fact, be maintained. Maybe people are just taking a breather. I hope that's the case.

As Rose Red said in the Katy books -

Feb. 24th, 2026 04:34 pm'I'm so glad I didn't die with the measles when I was little!'

Thinking a bit further about that education meme and the line You were in relatively good physical and mental health.

Well, on the one hand, I had my vaccinations for smallpox, diphtheria and whooping cough all in order at a young age.

I did, however, get measles, chickenpox and mumps once I started school and they were going around. And in those days if you had an infectious disease you were obliged to stay off school for a designated quarantine period (and return your library books to the Public Health Department for fumigation).

I think scarlet fever was still around though rare, and I have a vague recollection of some child at the school actually dying from it?

Polio vaccination only came in when I was 7 or 8.

I suffered from severe tonsillitis until they removed them when I was 6, I am not at all sure, in the light of present thinking on the subject, that this was necessary, but it was very common.

In less dramatic health interventions, I mention the free codliver oil, orange juice and milk bestowed by a munificent government.

I am a little surprised, in retrospect, that my short sight wasn't picked up through testing at school, but in fact my mother noticed me squinting at things and took me for an eye-test.

I feel that I had fair amounts of time off from school being ill one way and another (besides the aforementioned epidemic diseases and operation) - not to mention the appendectomy and its after-effects when I was at uni - but that this didn't have any major adverse impact.

At the grammar school I was tagged for remedial exercises to do with the way I walked (on the outsides of my feet?): am not sure this had any effect whatsoever.

My migraines were not identified as such.

Period pains were after the way of womanhood, pretty much.

On the whole, relatively good health. A certain amount of mental stress, especially at uni.

Well, I spent 40 hours at work

Feb. 24th, 2026 09:16 amFor everybody at home, leaving without a replacement is not simply a fireable offense but an actual, factual crime. Also, I'm not sure how I would've gotten to the bus. I mean, it's right outside the door, and buses were running all night, but man, it was brutal out there. We needed a little shoveling, and neither I nor manager wanted to shovel, so we had to wait for the neighbors to get their sidewalks and then sorta patch us into theirs. (The transportation issue is also why I'm not blaming any coworkers who didn't come in. It was impossible. I genuinely don't think that this was a fixable issue, Staten Island got a lot of snow.)

In retrospect, what probably ought to have been done would have had to have been done in advance:

1. Manager should've taken as much discretionary money as possible, agreed to let staff order Chinese or whatever for two, three meals - something that reheats nicely - and offered to pay all our carfare home in advance, and then used that to straight up bribe at least one extra staff member to stay over the storm. With three of us, we could've had one on each floor and also could've more easily arranged sleeping shifts so somebody was awake at all times.

2. She also should've called up the families of those residents who frequently go home for an overnight and asked if they'd take their relatives from Sunday afternoon until Tuesday afternoon or Wednesday morning. That's suboptimal for a lot of reasons - there's a reason they all live in a residence instead of with their families! - but it would've lightened the burden on us significantly if we'd had even just our two or three easiest residents away visiting their sisters and brothers.

But we all survived! My replacement actually showed up at midnight last night! But she declined to wake me on the grounds that I wasn't going home at midnight, and she was quite right. And then another staff member showed up this morning, and 90 or 100 minutes later my bus finally showed up. (And yes, I do insist on getting paid for that last hour and a half as well. I wasn't just sitting around, I was doing laundry, and supervising on the basement so that everybody else could handle the upper floors, and walking the guys out to their van so nobody slipped on ice.)

I'm home now, I showered, and I have the rest of the week off, off, off. Yay me!

If this happens again, I'm bringing a change of clothing.

The Rift by Walter Jon Williams

Feb. 24th, 2026 09:15 am

The New Madrid Fault teaches a memorable lesson about the transience of things.

The Rift by Walter Jon Williams

Trying Out A New Recipe: Ash Baber’s Bolo Gelado de Brigadeiro

Feb. 24th, 2026 03:26 amI can honestly say I’ve never heard of Bolo Gelado de Brigadeiro, or any of the words that make up this Brazilian dessert’s name, but when I came across the reel of Ash Baber making it on Instagram, I knew I wanted to give it a whirl.

Determined to try this chocolatey confection for myself, I went over to his website and took a look at the recipe. When you first look at this recipe, it looks very long and decently complicated. There’s three different sections, each with their own list of ingredients. While there are a lot of ingredients, if you look at them individually they’re really not that wild, it’s just that there’s a lot of them. What is wild is that there is butter, eggs, and oil, as well as white sugar, brown sugar, and sweetened condensed milk, so it really ends up feeling like you need a ton of stuff to make one cake.

Determined to try this chocolatey confection for myself, I went over to his website and took a look at the recipe. When you first look at this recipe, it looks very long and decently complicated. There’s three different sections, each with their own list of ingredients. While there are a lot of ingredients, if you look at them individually they’re really not that wild, it’s just that there’s a lot of them. What is wild is that there is butter, eggs, and oil, as well as white sugar, brown sugar, and sweetened condensed milk, so it really ends up feeling like you need a ton of stuff to make one cake.

You have to make the brigadeiro, make the cake, make the milk soak, and put it all together.

So, was it worth the hassle? How long did it really take? And, of course, how many dishes did I make in the process?

Let’s start with the cost of ingredients. Like I said, nothing was too out of the ordinary, so everything was easily attainable from my local Kroger. The only thing I would say I don’t regularly have on hand on this list is buttermilk, and it’s a 50/50 chance on whether or not I have heavy cream on hand. However, I happened to be out of a lot of things I normally have, so I had to buy some stuff for this recipe I generally would’ve just had.

I bought two cans of condensed milk, and I buy the Eagle brand one, so those were $3.49 each. Usually I have at least one can of sweetened condensed milk on hand, but I still would’ve had to buy one anyways since the recipe calls for two. I only bought a pint of the Kroger brand buttermilk, so it was just $1.29. For the Kroger brand heavy cream, I went ahead and bought a quart, so that was $5.99. Normally I have plenty of butter, but I was completely out so I got two 2-stick packs of Vital Farms Unsalted Butter. I also normally have vegetable oil, but I was down to about one tiny splash, so I bought a new 40oz Crisco Vegetable Oil for $4.79.While I did have eggs, the recipe calls for six (which seems like a lot) so I had to buy a new pack, and I bought Pete & Gerry’s Organic Free Range eggs for $6.99, but you could easily cut down on this cost by buying the Kroger brand large white eggs for $1.79. Also, this one is optional, but I bought Simple Truth Chocolate Sprinkles for $2.69.

All of that came out to $28.73. Not horrible but not cheap, either.

After acquiring the ingredients, it was time to make the brigadeiro:

I know this is only the first photo of many, but I forgot to include the actual chocolate in the photo. It was Ghirardelli. And then upon making I came extremely close to forgetting to put in the condensed milk. I was very scatterbrained apparently.

This part, while easy, was definitely time consuming. I felt like it took longer than I expected for the mixture to thicken up, but I also feel like maybe I didn’t make it hot enough at first. I think I was nervous to burn the cream so I tried to keep it pretty medium-low, but it wasn’t really thickening up much until I turned it up a bit. Technically the recipe doesn’t say how long it takes, but it took me about thirty minutes, and I was constantly stirring it, so that was tedious.

After it had thickened up to the point that I can only describe as “probably good enough,” I set it aside to cool a bit before putting some cling wrap over top and putting it in the fridge to chill.

Here’s the layout of ingredients for the cake portion:

Thankfully, this was basically just “throw everything in your stand mixer bowl and whip it together.” I put the cocoa powder and instant espresso powder (I know the recipe calls for instant coffee, but I assume this recipe can only benefit from the substitution) in the bottom of the stand mixer bowl first, then poured the hot water over it and whisked it into a smooth, thick paste:

I tossed everything else on top of it and got to mixin’. Here’s what we were looking like before the addition of the eggs and the buttermilk:

This was pretty damn gloopy, and weirdly grainy.

And after the addition:

The mixture was much more airy and light now, more like a fluffy texture. Almost mousse-like, but not quite at that level of lightness.

I opted to mix the flour in myself rather than with the stand mixer, because the bowl was honestly really full and it was a lot of flour. I didn’t want it to go exploding everywhere in the stand mixer.

When I started mixing the flour in, tiny clumps of flour started appearing all throughout the batter, like they didn’t quite mix in right. Definitely was starting to wish I had sifted the flour. I beat the clumps out best I could and poured it into the cake pan, then put it in the oven for one hour at 350 degrees Fahrenheit. There was so much batter in the pan that I was worried not even an hour would cook the cake all the way through, but when I used a knife to test it fresh out of the oven, it came out perfectly clean.

Putting that aside to cool, it was time to make the milk soak, which is just milk, cocoa powder, and sugar.

Once the cake and milk soak were both cooled, it was time to take the brigadeiro out of the fridge and put the whole dang thing together. Here’s the brigadeiro all thickened up:

Gawd dayum was this thicc. Rich and fudgy and oh so chocolatey. It was honestly incredible, but I was sure I was about to bend my spoon trying to mix it around. Handle with caution.

The cake cut in half easily, as it was very tall and made two very nice layers. I put the bottom layer in the cake pan I had baked it in, then poured half the milk soak over it. Scooped half the brigadeiro onto the first layer and smoothed it out over the surface, then slapped the top layer on top and poured the rest of the milk soak over it (I docked the top a bunch with a fork so the milk could go into the holes), and slathered that bad boy in the rest of the brigadeiro. There was so much brigadeiro on top, the cake pan could barely even contain my creation, the fudgy topping starting to spill over the sides.

The instructions say to let this puppy sit in the fridge overnight, and though it was hard not to slice right into it, I managed to let it rest in the fridge.

Once I took it out (it was heavy) and put sprinkles on top, it was glorious:

In the moment, I thought that was plenty of sprinkles, but looking at it now, I totally could’ve put more. It looks a little sparse.

I was eager to cut into it, and here’s the cross section:

My parents and I tried this cake at the same time and oh my gosh. It was probably the best chocolate cake I’ve ever had. I don’t even really like chocolate cake that much, but this one was so moist and rich, dense and fudgy and absolutely decadent. It was the kind you could only take a small slice of, and even then I needed some milk with it. It is not for the faint of heart, but it is for the fat of ass.

I had four of my friends try this cake and they all said it was incredibly banger, and even “dangerously good.” I was feeling pretty good that this turned out so yummy.

I will say this cake slides around a lot. The layer of brigadeiro in between the top and bottom cake layer make this thing slip and slide all over itself, and you can end up with a very slanted, divided cake if you aren’t careful. Cutting into it is messy, frosting it is messy, divvying it up into Tupperwares to give to other people is messy. But boy is it delicious.

For the dishes portion of this recipe test, this recipe is unique because it isn’t measured with cups and the like. You can measure everything on a digital scale, which made everything so much easier and made me use considerably less dishes. I used one bowl to weigh the brigadeiro ingredients in, one pot to cook the brigadeiro in, a rubber spatula to mix it, and another bowl to put in the fridge after it cooked. For the cake I used my stand mixer bowl, one attachment of the stand mixer, one whisk, a teaspoon, a tablespoon, and one rubber spatula to put it into the cake tin. I guess you can also count the cake tin in that, too. Oh, and a bowl for the eggs because I always crack eggs into a separate bowl first instead of straight into the cake batter. Finally, I used one small pot for the milk soak, a tablespoon, and another rubber spatula.

So, was it all worth it? The large ingredient list, the time that went into it, the dishes, and the cost (roughly, prices will vary for you, obviously).

I think yes! But this is definitely something to make for special occasions, or maybe for something like the holidays, when you need something to feed a lot of people. This cake makes a lot of cake.

I honestly liked making this cake and I’m very happy with the result. The dishes really weren’t so bad, and the praise you’ll get for how good this tastes outweighs the considerable effort of making it.

Have you heard of this dessert before? Do you usually like chocolate cake? Let me know in the comments, and have a great day!

-AMS

Bundle of Holding: Mists of Akuma

Feb. 23rd, 2026 02:10 pm

A bundle for Mists of Akuma, the tabletop roleplaying campaign setting of Eastern fantasy noir steampunk from Storm Bunny Studios for Dungeons & Dragons Fifth Edition.

Bundle of Holding: Mists of Akuma

The Big Idea: R. Z. Nicolet

Feb. 23rd, 2026 06:21 pm

Heroes come in many sizes, shapes, colors, and… fabrics? Author R. Z. Nicolet is here to show that your choice in clothing can be more than just stylish, it can be functional, perhaps even magical. Don your finest accessories and check out the Big Idea for her newest novel, The Cloak & Its Wizard.

R. Z. NICOLET:

Have you ever been reading a book or watching a movie when you really wished you had a different character’s perspective on events? Maybe wondering what the tavernkeeper thinks of the rowdy adventurers or what the aliens think of the bumbling human explorers?

Some of my favorite books are those that literally take an alien viewpoint – like Chanur’s Pride by C. J. Cherryh or any number of recent novels by Adrian Tchaikovsky. What would it be like to see the world through another set of eyes? Or none at all?

Years ago, I watched Doctor Strange. It was fun, but Strange was Iron Man with magic and not that interesting. I was more intrigued by the other characters, especially the Cloak of Levitation. What was its story? What did it want out of existence? Why did it decide that this random sorcerer was worthy of its attention? When it gets muddy, does it go in the laundry?

I was in the middle of a very serious fantasy thriller manuscript, but I decided to write one chapter of something lighter. Just for fun. I took Doctor Strange, filed the serial numbers off, and out came a scene about the Cloak of Sunset and Starlight deciding that newly minted wizard Veronica Noble needed better outerwear (much to her chagrin) with as much snarky commentary about human foibles as I could pack in.

Just one chapter.

One chapter turned into two, which turned into three.

At this point, I realized I had a serious problem on my hands.

I’m normally an outliner. I start with plot and then cast my characters in the requisite roles. This time, I was doing it backwards: the vain and mischievous cloak came first.

The tricky part was turning the amusing sidekick into the lead. To emphasize the depth of the challenge: the folder on my computer that’s got all my drafts and notes is named “Untitled Cloak Book,” a reference to the video game featuring a notoriously chaotic goose.

Supporting characters have an advantage: they can be flavor instead of substance. Like Strange’s Cloak of Levitation, they show up as a convenient plot device or a humorous diversion and then fade into the background. They don’t have to make the hard decisions or save the world. Quirks don’t linger long enough to become grating. Character development is optional, as is backstory.

If I wanted to keep the cloak at the center of the narrative, I needed it to be more than just the sidekick.

A part of the solution was to let Noble, the wizard, act as the cloak’s foil. She’s the serious, dutiful contrast to the cloak’s love of excitement and drama. Her reluctance to act gives the cloak reason to intervene.

The rest was treating the cloak like any other main character. When I got to editing, I had to adjust those first few chapters to make sure the stakes were clear – and that it was the cloak dealing with them. The how is very different from a human character, but many of the deeper why reasons are similar – from wanting an interesting life to protecting its friends.

Perhaps that’s the real Big Idea: however peculiar the perspective, they’re still a person trying to be the hero of their own story. (And hoping to avoid a trip through the laundry machine.)

The Cloak and Its Wizard: Amazon|Barnes & Noble|Bookshop|Powell’s|Kobo

That educational privilege meme thing

Feb. 23rd, 2026 06:16 pmAnd I'm not at all sure it's culture-neutral, hmmmm?

Okay, I had parents who had books in the house and read to me and once I could read took me to the local library to get tickets for the children's department.

No children's museums that I recall but visiting the rather dull local one attached to the public library, and visits to local sites of historical interest.

My primary school was not, I think, particularly distinguished - suspect that the year there were a whole four of us passed the 11+ was Memorable - but there were some good teachers.

I don't know how one calibrates into all this my mother knowing the teacher of Infants 1 and asking her about whether I could go to school once I had turned 5 (having an autumn birthday) and her saying, oh, send her along, on account of my mother thinking I was entirely ready.

And then the Head saying I should do the 11+ technically a year early - (which was not a given, people did get kept back)

Going to a fairly academically-intense girls' grammar school, where I did get the odd spot of class-hassle, I realise in retrospect (including from horrid Mrs B of the really weird ideas about sex), where I was marked out as university material and my parents exhorted to keep me on the sixth form -

Which they were entirely happy to do.

So yes, I was I suppose supported on my academic journey. But some of that was external factors, like the existence of that extinct phoenix, full student grants.

The Immortal Gifts Podcast: Episode 5

Feb. 23rd, 2026 05:02 pmLudwig’s Tale

Welcome to The Immortal Gifts Podcast, where Dave Robison, Veronica Giguerre, and J Daniel Sawyer read my novel, Immortal Gifts, to you. In episode five, Ludwig tells his side of the story.

Impatient? The audiobook is available in my shop and headed to all the places audiobooks are sold, and my Patreon is a week ahead.

Counter-programming the State of the Union

Feb. 23rd, 2026 05:00 pmSo, tomorrow—Tuesday, 24 February, 6:00 PM PT/9:00 PM ET—I’m doing a virtual book event for City Lights in San Francisco. I’ll be reading from She is Here, and talking with the editor, Nisi Shawl, about the book, the editing process, and—yes!—politics. What, you’re surprised? Come on, it’s City Lights; the Outspoken Author series, “designed to fit your pocket and stretch your mind,” is all about “today’s edgiest fiction writers” showcasing “their most provocative and politically challenging stories,”; and, well, the State of the Union. How could we not get political? Therefore, as well as poems and art and fiction, we’ll talk about manifestos and activism and what role writers can play in creating change.

So what would you rather listen to for ninety minutes: lively book-and-art-as-activism chat, or some bloated rambling about the (very sad) State of the Union?

Assuming you know the right answer, you can register here: it’s free and open to all.

See you tomorrow!

Snow shows no sign of stopping

Feb. 23rd, 2026 11:45 amI mean, the buses are running, but nobody else is coming in, and it’s not a job you can just shut down for the day.

The Essential Patricia A. McKillip by Patricia A. McKillip

Feb. 23rd, 2026 11:00 am In “What Inspires Me,” Patricia A. McKillip’s WisCon 2004 Guest of Honor speech, and penultimate entry in The Essential Patricia A. McKillip, the award-winning fantasy writer said: “What I set out to do about fifteen years ago was to write a series of novels that were like paintings in a gallery by the same artist. Each work is different, but they are all related to one another by two things: they are all fantasy, and they are all by the same person” (p. 298). That’s the best possible summary of what this new career retrospective is, I think, though of course it’s made of short stories and not novels. It’s an excellent primer on McKillip’s themes, threads, preoccupations, imagery, and style, as well as her incredible range. And it led me to reflect on some of her intersections with other writers, too.

In “What Inspires Me,” Patricia A. McKillip’s WisCon 2004 Guest of Honor speech, and penultimate entry in The Essential Patricia A. McKillip, the award-winning fantasy writer said: “What I set out to do about fifteen years ago was to write a series of novels that were like paintings in a gallery by the same artist. Each work is different, but they are all related to one another by two things: they are all fantasy, and they are all by the same person” (p. 298). That’s the best possible summary of what this new career retrospective is, I think, though of course it’s made of short stories and not novels. It’s an excellent primer on McKillip’s themes, threads, preoccupations, imagery, and style, as well as her incredible range. And it led me to reflect on some of her intersections with other writers, too.

As far as themes and threads go: A prominent one is women who are trapped by their roles, by a lack of opportunity, and by men. These men are sometimes well-meaning and clueless—but often they are mean and even cruel, dismissive and neglectful, and closed. Men who don’t ask questions, who assume things about the women and the world around them: what they are like and what they are capable of and what they mean. Many of these stories (and a lot of McKillip’s work in general) are romantic and end happily (as she alludes to in “Writing High Fantasy,” the final entry in this anthology); but it’s the men who are willing not just to think, but to reconsider, who find happy endings. These men put metaphors together and uncover different perspectives, and they allow other people to know more than they do. The exception to this lies in the more fairy-tale or parable-feeling stories, like “The Lion and the Lark,” in which the man is a magical entity and doesn’t do a whole lot of learning or changing. But in “The Lion and the Lark,” the man at least does a good job of knowing and loving the protagonist.

The fairy world appears often, posited as a secret world. And here’s another of the collection’s threads: secrets, and particularly secret identities and their discovery. The majority of these stories have at least one character who isn’t who they seem to be, or who isn’t sure themselves who they are. There’s often a lot of intersection between secret identities and secret worlds, or sometimes simply a different, secret, way of things. Indeed, the most important hallmark of McKillip’s style, I think, is her particular mix of solidity and dreaminess. Her characters feel like real people, with practical concerns, who you could imagine stubbing their toes or running out of groceries—things that are mundane but also specific to them and their world. But these solid characters exist in much more fluid worlds. Her settings and plots are both held together by feeling, evocative description, and character, and so sometimes they’re vague and oddly shaped. Sometimes her novels can be a little loose and meandering because of that dreaminess, while some of the short stories in this collection end before I wish they did.

My two very favorite stories in the collection are “Lady of the Skulls and “Byndley.” Both of them exemplify this point about style in fascinating ways.

There’s something particularly powerful and rich about “Lady of the Skulls,” and I think part of that is due to how focused the setting is: a lone tower, filled with vast amounts of mythical treasure, standing far away from everything on a barren plain. Those who visit the tower are allowed to choose one thing to take with them. If they choose the most precious thing in the tower, they can leave freely; if they choose wrongly, they die as soon as they leave. The Lady of the Skulls is the woman who guards this tower and has to watch as men come and break themselves on it. She plants her flowers in old skulls. Her watering can is the helmet of some past adventurer.

I felt the awe of the magic here, and understood this woman as a particular, specific person. All of the complex elements and different flavors get to kind of marinate in this one specific place, which sits at one specific point in these men’s lives. We do get a flashback at the end, but it feels like a reward to me, not a break in focus, because it finally gives us the final piece we need to understand the place we’ve been in for the rest of the story.

In general, though, my favorite McKillip stories tend to sit somewhere in between her real-world style and her vaguest dream-like style. “Byndley” does exactly that. It is about a wizard named Reck who once fell in love with the faerie queen. The faerie queen invited him into the woods, and took him into her bed. But the queen has a husband, and Reck can’t help but be jealous. He steals a special gift that the king gave the queen: a “tiny living world within a glass globe” that’s astonishingly beautiful. Because he’s a wizard, he was able to escape, by jumping into the globe itself and making the globe vanish. Now, years later, he still has the globe.

“I took it partly to hurt her, because she stole me out of my world and made me love her and she did not love me, and partly because it is very beautiful, and partly so that I could show it to others, as proof that I had been in the realm of Faerie and found my way back to this world. I took it out of anger and jealousy, wounded pride and arrogance. And out of love, most certainly out of love. I wanted to remember that once I had been in that secret, gorgeous country just beyond imagination, and to possess in this drab world a tiny part of that one.” (p. 111)

But Reck doesn’t say this to excuse or defend himself. He explains this to one of the citizens of the town of Byndley, where he’s come on a quest to return the glass globe back to the faerie world. He cannot live in peace with what he’s stolen. He feels the weight of the queen’s memory—or his own guilt. So he searches far and wide for a way to give it back. And in his search, it turns out, he seems to have discovered something true about faerieland and about himself, something that applies to McKillip’s stories generally: Something about the porousness of worlds, and about what it means to be inside one or another, and how you can sometimes be in more than one place at the same time, in different ways.

In fact, Reck discovers that he’s never really left the globe at all. The town of Byndley is made up of faeries in disguise, and the townsperson to whom he told his tale was the faerie queen herself. When he leaves Byndley, he doesn’t look back: “He looked up instead and saw the lovely, mysterious, star-shot night flowing everywhere around him, and the promise, in the faint, distant flush at the edge of the world, of an enchanted dawn” (p. 116). This is how McKillip’s work makes me feel, too, and I think it’s what I want out of fantasy most of all (alongside characters to be there with me): the feeling of that promise of wonder and enchantment, and the truth of that feeling. Somehow, by giving the globe back, Reck gets to keep that feeling with him, which was what he really wanted anyway.

Stylistically, “Byndley” and “Lady of the Skulls” work particularly well because of the way they give us that feeling—they give us a world that we can feel that way about. It’s magical enough to be wondrous, but it’s also defined enough to picture at all. Sometimes, McKillip’s more real-world stories lose the wonder for me—“Mer,” for example, is this way, although I did really enjoy it. Others are so vague that it’s hard to get a grip on anything, though this is more true of some of her novels than of any of the stories in this collection. In The Book of Atrix Wolfe (1995), for example, there’s also a wizard who tries to travel between the fairy realm and the human realm. But that story is written in a much more dreamlike way, and also (maybe more importantly, even) the journey often takes place in Atrix Wolfe’s head. For much of the book, he has nobody to talk to about what he’s trying to do or what exactly is troubling him. In “Byndley,” Reck asks people questions all the time, so that even if we don’t get definite answers about what the world is like, we learn what the people of Byndley are like and what they think. In “Lady of the Skulls,” the two main characters ask each other questions, too. There’s something about that communication and the acceptance of wonder that really makes these stories come alive.

McKillip is unique; there’s no one else who you’d mistake for her. But she is deeply invested in fantasy as a genre, and fantasy in turn is often interested in interpretation and repetition (among other things). Le Guin is maybe the most obvious comparison, as far as feminism and the role of women in magic go (A Wizard of Earthsea [1968] notwithstanding; McKillip didn’t need to go through the learning curve that Le Guin did). Tanith Lee is also in there, and Angela Carter (Carter especially in “The Lion and the Lark”); and, a little bit more recently, Ursula Vernon—the matter-of-factness, the vivid lives of different unusual people (particularly women), the brand of humor. But “Byndley” in particular shows McKillip’s fundamental Beagle-ness.

Peter S. Beagle is an admirer of McKillip’s work and they collaborated on a novel; he also wrote the afterword to Dreams of Distant Shores (2016). Together, they’re two of my personal favorite writers because of their simultaneous true love of fantasy and reality—for the strangeness to be found within. McKillip is a little dreamier than Beagle is, Beagle a little more jokey and parodic, and Beagle’s women frustrate me sometimes, but that’s for some other review; but ultimately what we see in their fantasies is an unusual interest in people and in spaces-between.

Take, for example, McKillip’s “The Harrowing of the Dragon of Hoarsbreath.” This is a relatively early story. And Kushner’s introduction explains that Terri Windling commissioned it for her collection Elsewhere in 1982; it was McKillip’s first published short story for adults. I like how surprising it is, and how funny it is. The characters are taken seriously—it matters who they are and why they think and feel the ways they do. What happens to them isn’t predictable, and nor is it predictable what the story focuses on and cares about. It’s excellent stuff. Likewise, in “The Witches of Junket,” the characters are great and at the very centre of the story, alongside a really fascinating portrayal of witchiness. The POV character in particular is one of McKillip’s excellent older women. If the story gets a little bit jumbled up, and the pacing is a little bit too fast—there are too many new characters and I would’ve loved the time to get to know them a little better, and to more clearly understand what was at stake—this can be forgiven because of the connection it makes between reader and characters.

“The Witches of Junket” is set in our contemporary world, as is “Out of the Woods.” This is another story that’s difficult to predict, but in this case that’s more because of what the story chooses to focus on than because of plot. The main character, Leta, is worked to the bone by her husband and by her magician boss, and we know that something must change. But that change is surprising, more melancholy than I expected, and somehow also exactly right. I wish this story had been longer, because I wanted to know what happens to the main character, but its abrupt ending is part of the point. Indeed, I’m not always very patient about shorter stories, especially when they hinge on ambiguity or some sort of “gotcha” moment, but McKillip almost always wrong-foots me. I have no idea what happens in “Weird,” for example, and yet I’m still thinking about it. I don’t feel irritated or upset about that, just intrigued.

Still, “Knight in the Well” is maybe the book’s primary example of McKillip’s dreamy vagueness: There’s a lot going on, it’s beautiful, and, again, I had no idea what any of it meant until maybe halfway through the story at best. This story, too, ends rather abruptly, and I would’ve enjoyed much more time with these characters instead of having their conflicts resolved so fast. In contrast with “Weird,” however, this is one of the volume’s longer stories, at around fifty pages. “The Gorgon in the Cupboard” is of similar length, and likewise I wanted more perspective from it: on the story’s women, as well as more information about the titular gorgon, who in a way was the least interesting part of the story. If the shorter stories can feel too brief, both of these longer stories feel a little bit structurally lopsided—and so also somehow unfinished.

Why are these stories the length that they are? Why not longer or shorter? I wonder what was going on with these stories; were they written for some purpose in particular? I would love more background information on them. This is perhaps my one real criticism of the present volume: I would have liked more information on the stories, and more information about the logic behind the anthology itself. It’s a lovely book, and all of the stories deserve to be here and to be read carefully. I’m just not sure what makes this collection the “Essential” McKillip, especially when compared to Tachyon’s earlier (and also excellent) McKillip anthology, Dreams of Distant Shores. With a title like this, I’d have liked there to be an explanation of why these stories, and not others, are so definitive.

For instance, “Wonders of the Invisible World,” collected here, is the title of another McKillip anthology, and so we might assume it has significance. In the story (which shares its title with a book by Cotton Mather, the seventeenth-century Puritan), a researcher from the far future goes back in time and pretends to be an angel that Cotton Mather saw in a feverish revelation. Her boss has sent her there because he’s trying to write a history of imaginative thought—and, in their far future, everything possible to imagine has already been imagined by a very powerful computer. The researcher isn’t allowed to veer from her script, which is set to minimize any alteration of the past, even though she very much wants to. When Cotton Mather raves about witches, it’s difficult for her to stomach. But she’s supposed to keep the angel within the limits of what Cotton Mather would have imagined the angel to be.